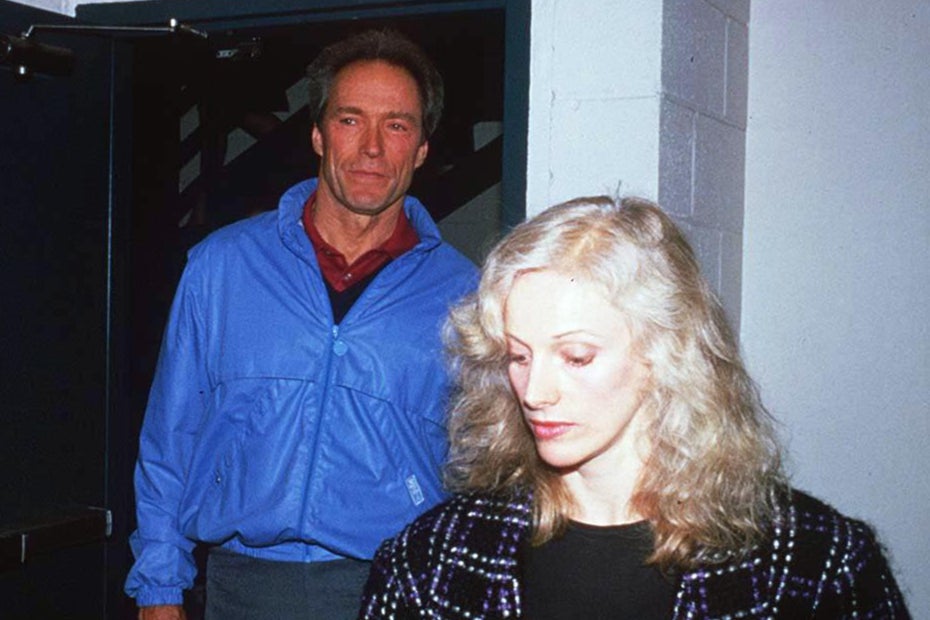

Sondra Locke, Clint Eastwood and the tragic disappearance of a Hollywood icon

sOndra Locke didn’t like to tell people the year she was born. The American actress and director’s death in 2018 took six weeks for news to come out, so she probably wanted to keep that a secret as well. It had a certain quality to it. Unusually, mysteriously, neither here nor there, Luke can appear pale and boyish or strikingly feminine. They may appear old or ageless; Humankind either descended to our planet from the far reaches of space. She was one of the most fascinating characters in 20th century cinema. You may have never heard her name before.

In 1969, Locke received an Academy Award nomination for her first film, a largely forgotten adaptation of Carson McCullers’ novel. The heart is a lonely hunter. She followed that by playing one of the first transgender characters in American film in the thrilling psychological thriller Reflection of fear. This difficult pivot reflects Luke’s tastes, her disinterest in the Hollywood game, and her unconventional approach to life and love.

For that matter, she has been happily married to a gay man for over 50 years, 13 of which she spent cohabiting with her most prolific on-screen partner, Clint Eastwood. It was a love story that would help, then derail, and then cruelly define her career, with one American magazine referring to her as little more than “Eastwood’s embittered ex” in the headline of its obituary. She also made her own films, earning a seat in the 1980s boys’ filmmaking club, by doing work that no one else would dare do, for better or worse.

People eventually figured out Luke’s age: she shaved off a few years to get the role Lone hunterThen continue the dance. Luke’s 80th birthday would have been May 28. It probably passed without fanfare. But what if that doesn’t happen?

Locke is part of a lineage of female creatives—among them the late screenwriter Diane Thomas and producer, writer, and production designer Polly Platt—who smuggled their way into the American film studio system in the 1970s and 1980s, then faded into relative obscurity. Mystery then. But the act of Luke’s disappearance had its own characteristics. As a movie star, she had a degree of power in the industry that many of her fellow female filmmakers did not enjoy. But she also had a very famous boyfriend in Eastwood, and as their relationship crumbled, she found it impossible to crawl out from under his shadow.

In her acting work, Locke possessed a gentle, charismatic strength that came across as fragile or intimidating depending on the role. The heart is a lonely hunter And Reflection of fear, released in 1968 and 1972 respectively, depicts her as bored outsiders, teenage girls endowed with innate buoyancy, yet supernaturally hardened by life. In the psychedelic thriller Game of Death, produced in 1974 but not released until 1977, Locke is one of two psychotic women who take a man hostage when they show up on his doorstep. It’s breathtaking, wide-eyed, erratic and exciting. But it’s less interesting in the 1970s Willard, where you play the third wheel of a boy and his army of mouse friends. (Yes, more mice!) And disappointingly, it’s probably her most famous film that doesn’t star Eastwood.

I had a life before Clint and I intend to have a life after him

If none of these films propelled Luke into the A-list, it was probably due to bad timing. It is significant that her career seemed to falter with the arrival of Sissy Spacek, who was also a vulnerable alien beauty, but had the good fortune to go off in much better films. “I learned quickly that it doesn’t make much difference whether you’re the best at the role, or whether you have talent,” Luke once said. “It is a matter of something strange and indescribable.”

Eastwood entered Locke’s life during a professional lull. Desperate for a break, she takes a pay cut to star in his revisionist Western Outlaw Josey Wales in 1975. Like many of Eastwood’s leading ladies, Locke’s character was sharp and sassy—but doomed. Yes, you’ll be able to escape with the hero in the end, but only after experiencing the brutality first. Horrifyingly, her characters were gang-raped or nearly gang-raped in four of the six films she made with him.

She wrote in her diary in 1997 The good, the bad and the very ugly She and Eastwood were instantly smitten with each other. It also didn’t matter that they were involved with other people: Locke was in a platonic marriage with her lesbian friend, whom she had known since she was a teenager, while Eastwood was married to a woman. I don’t live with and it is said that he hardly saw. No matter how unusual it was, it worked.

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/month. After the free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

Watch Apple TV+ free for 7 days

New subscribers only. £8.99/month. After the free trial. Plan auto-renews until cancelled

Try for free

On screen, Locke played opposite Eastwood and a bleak orangutan In every way but loose and its sequel, but she played other characters of increased strength and complexity. the challengereleased in 1977, oozes angsty charm as a gangster on the run, while being the vengeful antagonist of Eastwood’s penultimate Harry Callahan film. Sudden effect, in 1983. But their cooperation also left her trapped. “If you were in the Clint Eastwood movies, you were in the Clint Eastwood movie business,” Locke said in 1997. “She wasn’t part of Hollywood. That became clear early on. People stopped calling. They automatically assumed I was working exclusively with Clint.

This tension worsened over time. “You get into a mess because of your association with Clint… You get into a mess because you’ve been here a while, and everyone wants the new girl on the block,” she said in 1983. “In order to get out of this predicament.” Those grooves, you have to have your own idea, your own project.

It was the project Rat Boy, a bizarre Hollywood satire about a lonely window designer trying to monetize a half-mouse, half-human she stumbles upon in a dumpster. It’s ambitious but it’s a complete failure, like at meet Pretty woman. There are shades of Locke’s personal frustrations in the text, and sharp observations about celebrities and outsiders. But also a lot of chaos. “what is the point?” asked critic Roger Ebert in his review of the film. “Rat Boy Very strange, but not in an interesting way. Locke later said that the film was misunderstood by his backers at Warner Bros and cut into pieces in the editing room.

Meanwhile, Locke and Eastwood were outside. By most accounts, Eastwood is a person of few words, who has much in common with the elusive hucksters who made him a star. So imagine dating a guy. Interview with Eastwood published in The Independent In 1997, he portrayed him as a man who doesn’t end relationships — whether professional or romantic — so much as silently withdraws from them until the other person gets the hint. While Luke was in the early stages of filming it Rat Boy tracking Paid, a much better film starring Theresa Russell as an undercover cop who loses her senses, is called by Eastwood to inform her that he would like her to move out of their home in Bel Air. Luke was confused, and begged him to reconsider. He agreed and told her that they should postpone discussions about breaking up until Paid May wrapped. But when Luke returned home, she had changed the locks and put her belongings in storage.

“He had every right, if he didn’t love me, to end the relationship,” Luke said. The Independent, in the same Eastwood interview. “But he had no right to treat me like that. That’s where the line is drawn with Clint. He has all the rights and you have none. Meanwhile, Eastwood said he ended the relationship due to Luke’s marriage to boyfriend Gordon Anderson. He added: ” “She spent 98 to 100 percent of her time pampering him. She got bored of it. At some point, she says, ‘I want a normal relationship in life.’ I want a girl of my own.”

An unusual, year-long legal battle ensued, as Locke fought for alimony despite the fact that she and Eastwood were legally married to other people. Locke accused Eastwood of abusing her, and claimed that he ordered her to undergo two abortions and a sterilization – an allegation that Eastwood “vehemently denied”, while claiming Locke’s claim was “baseless and baseless”. In his own testimony, Eastwood would refer to Locke as merely his “occasional roommate.” Eventually, with Luke simultaneously exhausted by his breast cancer treatment, Locke settled, taking ownership of one house that Eastwood had purchased, with $450,000 (at the time, £251,000) in unpaid profits from Eastwood’s production company, and – Upon request – production. Directing the deal with Warner Bros.

While Locke initially declared victory, she later claimed that the Warner deal was a sham — she received $1.5 million and had an office at the studio, but more than 30 projects she submitted to them were rejected. Then I discovered that the $1.5 million secretly came from Eastwood, not Warner Bros. She filed a lawsuit against him for fraud. Eastwood claimed that his intentions were pure, and that he financed the deal to help Luke. She claimed it was a deceptive power play designed to trap her in the studio and keep her out of work.

The case went to trial in 1996, with Eastwood accusing Locke of using her cancer diagnosis to gain the jury’s sympathy, insisting the suit was merely blackmail. They eventually settled out of court for an undisclosed sum, and both parties insisted they won. While promoting her book in 1997, Locke admitted that she wished she had “understood who he (Eastwood) was” earlier. “I feel like, oh my God, I’ve lost so much time.” She said her book was an attempt to show her side of the story and reclaim the narrative that portrayed her as an obsessive gold digger. “I had a life before Clint, and I intend to have a life after him,” she said.

Luke’s career never recovered, and she said in 2013 that she believed she had been blacklisted as a result of her legal controversies. “No one wanted to get on Clint’s bad side,” she said. Wonder Star. “Why bother? Why get involved? I’ll always think I had a lot of admirers in high places, but they weren’t willing to put themselves on the line. That’s very expected in Hollywood.”

Little is known about Locke’s life in the following years. She remained married to Anderson and starred in one film, an independent romance titled Ray meets Helen, in 2017, but is otherwise dark. She was not included in the “In Memoriam” section of the 2019 Academy Awards, and Eastwood has made no public comment on her death from bone cancer. It is unclear whether they spoke again. Oddly enough, Eastwood’s 2018 film Mule He saw his character reconnect with his ex-wife whom he had rejected and abused, searching for redemption as she died of cancer. It was released in cinemas the day after Luke’s death was announced.

Every now and then, Luke’s name is called up in articles about the history of women in Hollywood — and several media outlets also revisited her battles with Eastwood during the high-profile confrontation between Johnny Depp and Amber Heard, a situation that had little impact. Parallels. But her actual work is worth revisiting too, no matter how funny much of it is. Locke was distinct, extraordinary, and brilliant, a woman born to a Hollywood that didn’t quite exist at the time she got there. But while he hurt her, he never broke her.

“In general, I’m happy with myself,” she said in a 2013 interview. “I feel like I faced the challenges I faced with a positive face like everyone else.”